Making ‘Living the Weather’

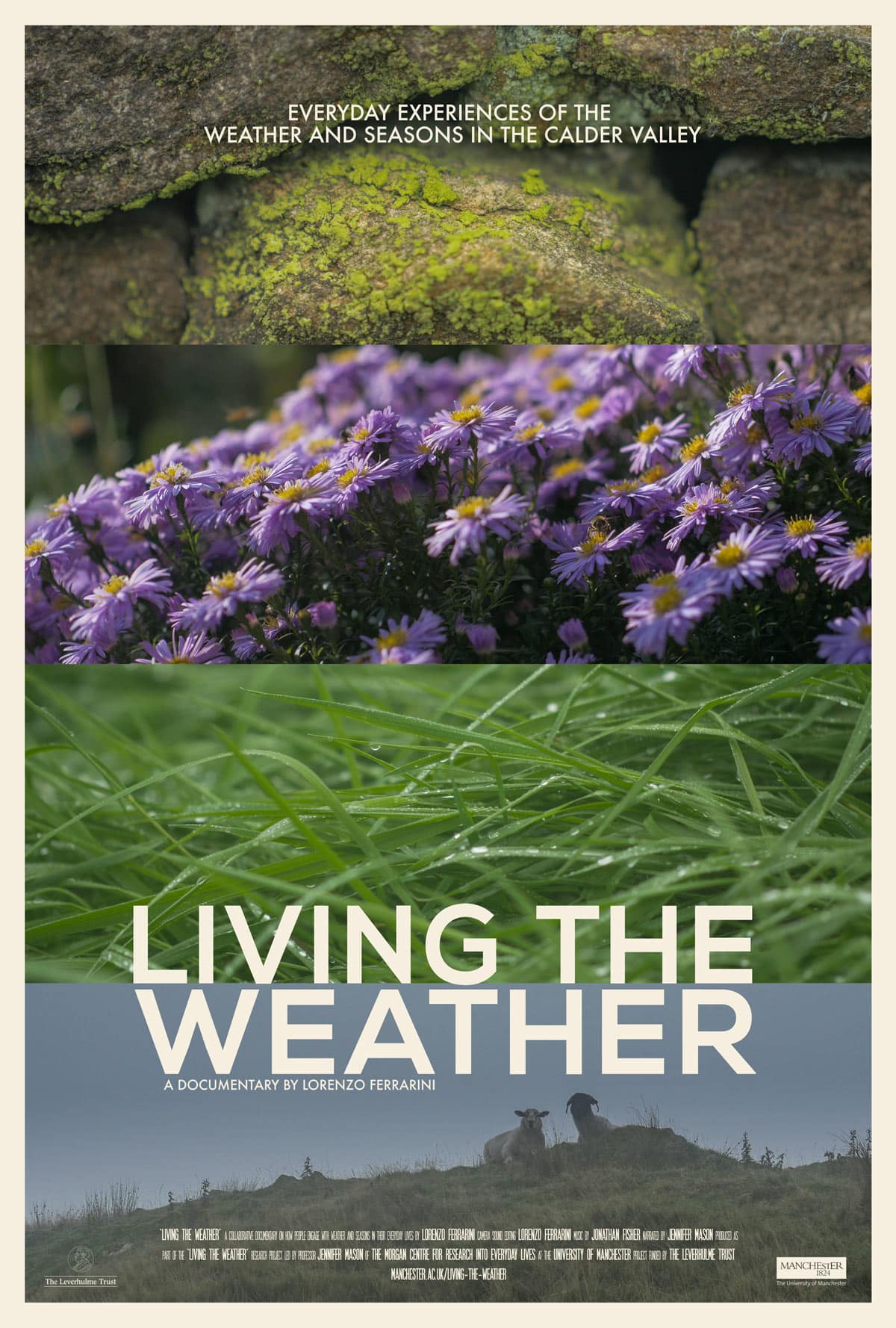

For the past 6 months I have been working as a filmmaker for Living the Weather, a research project funded by the Leverhulme Trust and led by Professor Jennifer Mason at the Morgan Centre for Research into Everyday Lives, Department of Sociology, University of Manchester. My task has been to realise a documentary film that could speak to the themes and approach of the research, providing at the same time an output and a place to experiment with ways of representing its theoretical ideas. I am currently wrapping up the editing of the film, which will be made public in late April. EDIT: the film is now available. In this post I describe the way I planned the film and how I produced it.

The Project

From the project website: Living the Weather is exploring how people ‘live’ the weather and seasons in their daily lives and relationships. Weather is said to be a British obsession, and it is well known to be a popular topic of passing conversation. But this project is looking more deeply, at how weather and season become ingrained in us, or get ‘under our skin’. It is exploring how weather and the elements shape our character, our memories, and our outlook, as well as our neighbourhoods and landscapes. It is investigating the role of weather and season in our relationships with others and with the places where we live, work and spend time. It is exploring how weather feels and how we experience it with all of our senses, as we go about our daily lives. The project is based in and around the Pennine Town of Hebden Bridge in the Upper Calder Valley of West Yorkshire.

I was very soon intrigued when Jennifer contacted me about the idea of making a film as part of the project, especially by the approach to the weather as something ingrained, implicated and interactive. In contrast to previous studies that treat atmospheric phenomena as an extrinsic force that affects people, influencing mood, living conditions, risk and even crime rates, Living the Weather proposes a focus on everyday experience and the perceived environment. This means that the way we live the weather and season is considered dependent on our past experiences, memories, current activities and approach to the surroundings. It resonates with my application of ecological perceptions to hunters in Burkina Faso, and in general with the topic of my PhD. I also found it an opportunity to develop my ideas on perception and recording, making of the film an experiment in sensory ethnography.

Pre-Production

I am used to developing a filmic form after long periods of fieldwork, deciding on formats depending on the kind of interactions I had with my subjects, the main themes I encountered and the specificities of each context. I worked in this way with Egyptian migrants in Italy and with donso hunters in Burkina Faso. In the case of Living the Weather I wasn’t the main researcher but I was joining a research already in full swing and from which some clear findings were already emerging. Additionally, I did not have as much time as I would have liked to work with the subjects, since I am working full time as a lecturer in visual anthropology.

As a solution, I came up with a structure that I could repeat with various participants to create different sections of the film. Initially, the idea was to assign to each person a type of weather and an activity. At the end of summer 2015 I visited some of Jennifer’s informants who had expressed interest in the film project. We tried to individuate a type of weather and activity based on their daily routines and on the interview work they had done with Jennifer. It soon became clear that the idea of a single atmospheric manifestation for each person was too reductive, as it did not really make justice to the variety of everyday engagements with the weather. Still, it was important to have a visual variety that would clearly distinguish each chapter, or I would run the danger of creating too much repetition.

Visually and acoustically my mind was pretty set on dividing each section of the film in two parts, very distinct from each other. The first section, between 2 and 3 minutes in duration, would be a series of extreme close-ups of textures, surfaces and materials, in which details would emerge from an out-of-focus background, giving an impression of almost tactile presence. These would succeed to each other, basically as filmed photographs, without any camera movement, as the viewers listen to a voiceover.

The other section of each chapter would be constituted by a sequence shot, around 5 minutes in duration, filmed with an ultra-wide angle lens. These shots would follow the protagonist of the chapter in an uninterrupted slice of activity, revealing how they engage with their surroundings. I admit I was very much inspired by the trailer of The Revenant, and how its DP Lubezki manages to relate his subjects to the landscape. To stabilise the camera I used a 3-axis gimbal and a lens equivalent to 17mm in full frame photographic terms, to convey three dimensionality and presence effect. I also decided to use the cinematic 2.35:1 aspect ratio, in part to underline the film’s immersive intent and in part to echo my visual inspirations for this project, especially Ben Rivers’ remarkable Two Year at Sea.

This is an example of one such sequence, a take that didn’t make it into the film because I inadvertently filmed my own hand for a moment. It should give you an idea of the concept:

To fit this immersive cinematography I recorded sound from my own head, using a pair of DSM microphones in a Sound Devices MixPre into a Sony PCM-D100 recorder. The DSM microphones are omnidirectional and baffled by the head of the recordist, so they render a pronounced three-dimensional effect, not unlike a binaural technique. For this reason they are used by soundscape and even movie sound effect recordists. One advantage is the way one can record a very immersive, emplaced sound as a one man band, having in other words the hands free for the camera. Among the downsides, I later discovered, are the ease with which they pick up any noise produced by the recordist (including breathing) and the incoherence between sound and image when I turned my head but not the camera.

Production

I am used to working collaboratively in my documentaries, and Living the Weather was no exception. I found it important also to counter-balance the way I was imposing a preconceived structure onto people, so that they could carve their own space to influence the shape of the film. In this process I was facilitated by Jennifer’s previous work with the subjects, which includes asking people to produce texts – from diaries to blogs to weather correspondences. Those texts helped us find, together with each participant, an aspect of their everyday that could suit the theme of the film. Some of those texts, sometimes already prepared and sometimes written down for the documentary, constituted the voiceover that each participant recited over my images. Each of them was loosely themed, and included for example the effect of walking on the creative process of writing, the way running transforms the experience of a rainy day, and the changing perspective implied by a move from a large town to a remote cottage on top of a moor. I also realised other voiceovers starting from more traditional interviews.

We then agreed for a slice of their lives to be performed and filmed as a sequence shot, based on the everyday activities each participant would normally go about: walking the dog, driving to work, running in the woods. Given the peculiarity of the shot I had in mind, and its technical difficulty, this sometimes involved repetitions and second takes, so the collaboration of the participants was fundamental. The two sections with the two different visual languages are not meant to be in an illustrative relationship, rather the voiceover and the evocative close-ups are supposed to inform the way we experience the sequence shot.

The documentary was filmed on a Panasonic GH4 camera, recording in the 4K DCI standard. This is a choice I made to have the maximum flexibility in case I needed to stabilise the footage with a software (which mostly wasn’t needed) and to have the film in a future-proof format. In hindsight it was probably overkill, and proved to be quite resource-intensive to edit. At the same time, I can’t help thinking that the insane amount of detail present in each frame contributes something to the materiality of the images and augments the hyper-realist effect that I was researching with the ultra-wide lens and the extreme close-ups.

Matching my work schedule with the subjects’ and at the same time finding the right weather conditions for what we had agreed with each participant was quite a challenge. On the other hand the clear structure I had devised allowed me to optimise the shooting ratio and make the most of the footage.While I consider this film mostly a way to present the outcomes of a research, I believe it was also useful to Jennifer to provide additional material to her text-based methodologies and enrich the perspective on living the weather with a knowledge beyond text. With a longer timeframe it would be interesting to involve more participants, from a broader social spectrum, with different occupations and living conditions.

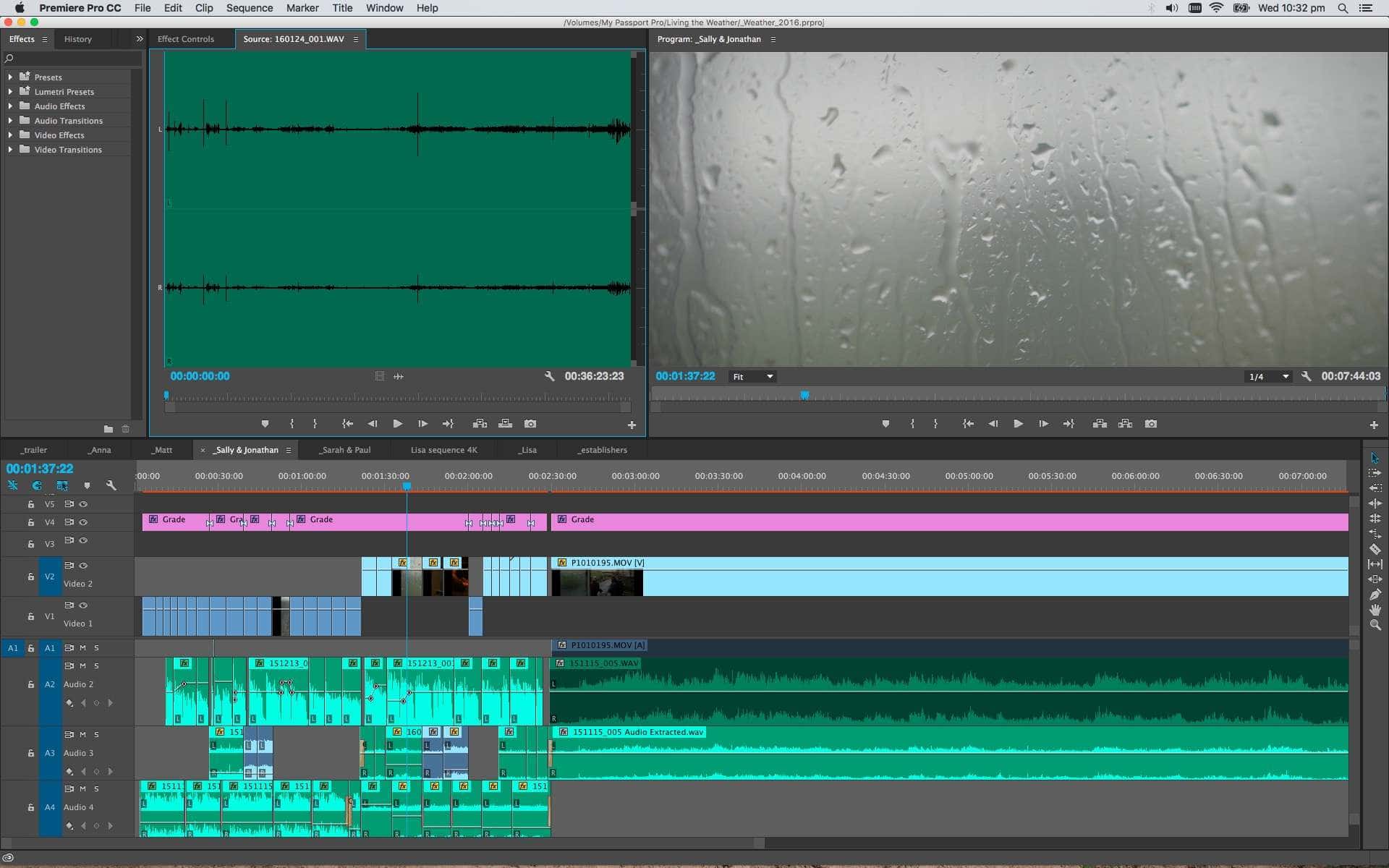

Post-Production

I edited the chapters of Living the Weather after each one was filmed, keeping the same format and respecting the time durations in a fairly strict way. In this way I was able to show them to the subjects and to the project leader. Having an idea of what each chapter looked like allowed me to understand what was needed from the following one, in terms of variety of weather conditions and themes. Together with Jennifer we have decided to tie the chapters through her own voiceover, in which she presents her point of view of researcher who lives in the valley and shares many of the same conditions as her research subjects.

The sequence shots simply necessitated a syncing of the audio recording and the image, plus some colour correction and grading. In general, because of the way I had decided its structure beforehand, this is not a film that changed much in the editing phase. However the initial sections with the close-ups and voiceover were more complex to assemble, especially from the point of view of the soundtrack. I layered the voiceover with a number of sound effects, many of which were wild tracks, in order to have a reciprocal reinforcing of images and sounds, contributing to the sensory qualities of the shots. I also had to resist the temptation to match the images and the text of the voiceover, which would have turned it into an illustration and neutralised the evocative and suggestive tone of the piece.

Living the Weather as sensory ethnography

The interest in visual anthropology for ways of evoking sensory environments and a knowledge beyond text has by now reached beyond the academia, mainly thanks to the success of the films of the Harvard Sensory Ethnography Lab. While these films, with the other main contribution on the topic represented by David MacDougall’s work, are certainly a source of inspiration for me, I wanted Living the Weather to take a different approach. I wanted my film to have a more interactive character, and be a place for dialogue and collaboration. To this end I used the voiceover section of each chapter, where participants had the opportunity to give a significant contribution to the film and shape their section according to their biographies and activities. In a work that is also about perception, it was important that I strived to integrate people’s points of view and avoid providing a mostly impressionistic portrayal of my perceptions.

The two elements that compose each chapter of this film embody two different approaches to sensory ethnography. The first is evocation, and I used it as a conjunction of close-up images and oral text. I believe that the linguistic dimension is not entirely antagonistic to sensory ethnography, provided it is exploited in evocative rather than illustrative ways. The second approach is immersion, which relegates language and information in the background – hence the recording techniques that in video and sound privilege width and dimensionality over clarity.

The film should be available freely online from next month, so watch this space if you want to know what the finished product looks and sounds like.